Using Digital Material

What is your story? The digitals you have may include texts, photos, videos, 3D models, audio, and 360-degree visuals. Once in good order, a lot of new possibilities open for you. What stories do you like to present? What is the perspective you want to highlight today? And for whom? You will find some samples here from the RETOLD case study. What can you do with your digitized material?

Case: Sharing videos & stories

There are many good reasons to use video, both for documentation and sharing. A short clip can be so appealing. Think for example of a cool craft event in your museum.

As for the story which goes with it, you can then add text for different target groups using artificial intelligence. Think for example of a text in Thai or simple English, or in a language for a niche group which seldom get your attention. When collecting the information for this craft activity through the RETOLD system, we gathered a lot of information. Not all is interesting for everybody, some is just for staff members or researchers. But even when taking the general public into account, there are different ways of telling the story, depending for example on the age.

Using AI (https://chatgpt.com) as tool we created 3 stories based on the same webpage (about Flintknapping).

"Long, long ago, people didn't have metal tools like we do now. Instead, they used stones to make things like knives and arrowheads. This was called flintknapping, and it was like a special way of shaping rocks so they could use them to hunt and build things. Imagine breaking a cookie into sharp pieces to cut something, that's kind of what they did with stones!"

For a 12-Years-Old:

"In ancient times, before people discovered how to make metal tools, they made tools out of stone through a process called flintknapping. They would carefully strike rocks, usually flint, to create sharp edges that could be used for cutting, hunting, and building. It was a skilled craft that required precision to make effective tools, and it was crucial for survival in the Stone Age. People in places like the Stone Age Park in Dithmarschen, Germany, still practice this ancient skill to show us how early humans lived and worked."

For a 65-Years-old:

"For thousands of years, before the advent of metalworking, early humans relied on a technique called flintknapping to create tools essential for their survival. By carefully striking stones like flint, they could shape sharp edges and points, which were then used as knives, arrowheads, and other tools for hunting, cutting, and daily tasks. This craft required considerable skill and knowledge, passed down through generations. The Stone Age Park in Dithmarschen, Germany, offers a glimpse into this ancient practice. By demonstrating flintknapping, they help us understand how our ancestors lived, worked, and adapted to their environment long before modern technology."

Phases of Flintknapping

1. Selecting the Raw Material:

The first step in flintknapping is choosing the right type of stone. Flint is the most common material because it breaks predictably and can be shaped into sharp edges. The stone should be free of cracks and flaws to ensure it breaks cleanly.

2. Core Preparation:

Once the right stone is selected, the next step is to prepare the core. This involves shaping the stone into a manageable size and form, often by removing some of the outer layers. The goal is to create a core that has a striking platform, where the toolmaker can hit to remove flakes.

3. Detaching Flakes:

The main part of flintknapping involves striking the core with a hard object, like a hammerstone or a piece of antler, to remove flakes. These flakes can either be the final tool or can be further shaped. The knapper must strike at the right angle and with the right amount of force to control the size and shape of the flakes.

4. Shaping and Retouching:

After the initial flakes are removed, the next phase is to shape these flakes into specific tools like arrowheads or scrapers. This is done by further refining the edges through a process called retouching, where small flakes are removed from the edges to create sharp, durable tools.

5. Final Touches and Sharpening:

The final phase involves fine-tuning the shape and sharpness of the tool. This might include more detailed retouching or even grinding to ensure the tool has the desired sharpness and balance.

6. Tool Use and Recycling:

After the tool is used, it might get damaged or become dull. In many cases, the tool can be reshaped or retouched to extend its usability. Flintknapping was an ongoing process, with tools often being reused and modified throughout their life.

This step-by-step process demonstrates the skill and precision required in flintknapping, showing how early humans transformed raw stone into essential tools for survival.

"Flintknapping, the ancient art of shaping stone into tools, holds profound significance in the study of human history and technological evolution. As demonstrated at the Stone Age Park in Dithmarschen, Germany, this craft was pivotal in enabling early humans to survive and thrive in their environments.

The importance of flintknapping lies in its role as one of humanity’s earliest technological advancements. By mastering the ability to systematically fracture flint and other hard stones, our ancestors could produce sharp-edged tools essential for hunting, processing food, and crafting other necessary items. These tools, ranging from simple scrapers to finely crafted arrowheads, were not only critical for day-to-day survival but also facilitated the expansion of human societies by enabling more efficient use of natural resources.

Moreover, flintknapping represents a key step in the cognitive and cultural development of early humans. The process required a deep understanding of material properties, precision, and foresight—skills that are hallmarks of complex thought. The ability to pass down this knowledge through generations also speaks to the social and educational structures of early human communities.

In a broader context, flintknapping underscores the ingenuity of early humans in adapting to their environments with the resources available to them. It laid the groundwork for subsequent technological innovations and set the stage for the more advanced metallurgical techniques that would follow in later eras. Today, studying flintknapping not only offers insights into the lives of our ancestors but also serves as a reminder of the creativity and resilience inherent in the human species."

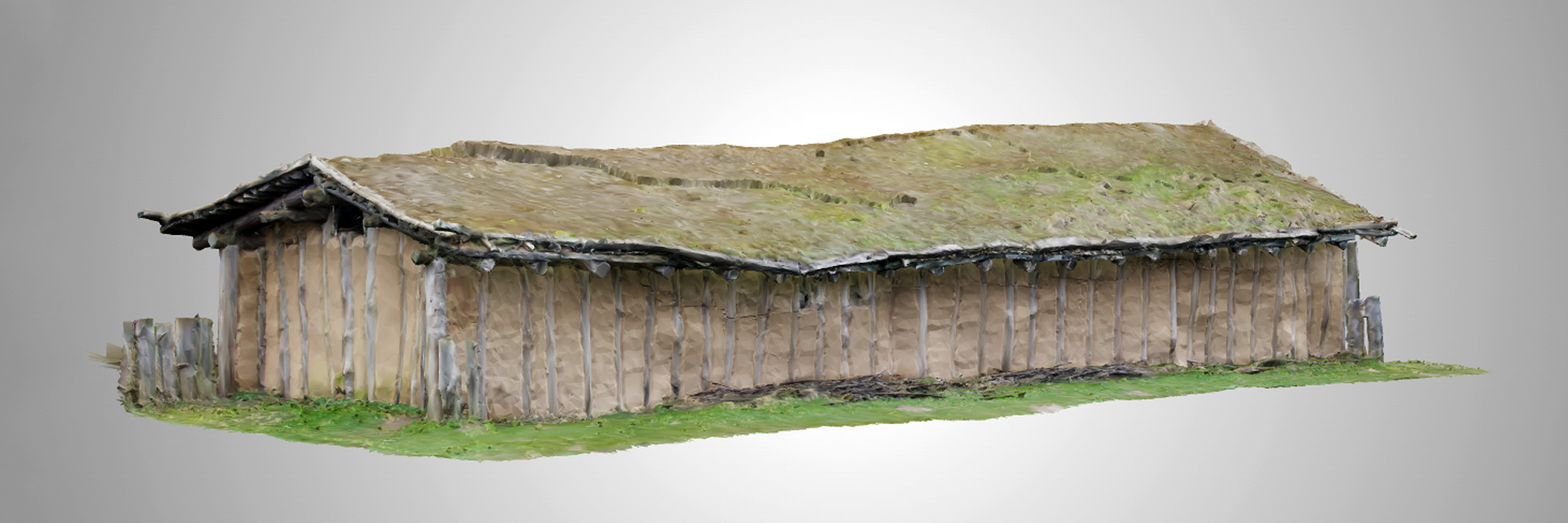

Case: 3D Models on your website

Once you pruced your 3D media you can share those in two ways:

1. Uploading the media to a sharing platform, or 2. Embedding media directly into your own website.

We discussed in detail what we thought would be most practical. What exactly can you do when you finally have that 3D model in your pocket? And what would that entail? For example, if we want to tell stories using that model as a stage, we need to make sure we have all the sources in order. This means going through our archives, checking details. Although quite different from what we are used to, the information we share this way is like any other story we share.

Both have their advantages and disadvantages, and choosing the best solution depends on what you and your museum are hoping to achieve. Is it more important for you to reach a large audience, or to present media to potential visitors in an informative way, or perhaps to share documentation with your scientific peers? Before planning on adding 3D models to their website or social media, the director of Steinzeitpark Albersdorf and the volunteer webmaster identified the challenges that had to be solved during the process... Read more

Case: Social Media posts

Sharing your story on social media is a must.

Depending on the channel, occasion, and target group, messages need to follow a certain structure (and length).

There are different ways of doing it, with simple images, video, or anything in between.

Flint Knapping as a craft

Tag:

#Steinzeitpark #retold #flintknapping #craft

In our open-air museums, we present crafts, but why? These crafts and their people tell a good story! Let’s take flint knapping in Steinzeitpark Ditmarschen, Germany as an example. Flint has been used for thousands of years. If you hit it, you get sharp edges which can be used for a wide range of tools and weapons. Because stone has been immensely important in the Stone Age, and because a lot of other materials are not preserved, the largest part of our history is called the Stone Age. When you visit the Steinzeitpark, you will find a lot of original flint tools exhibited there, but there is more! Here, you can see how flint tools were made, and they use replica tools every day! The most important techniques to make stone tools, are so-called hard and soft percussion, or in other words: hit the flint with something hard, like another rock, or with something soft, like a piece of antler or wood. Once you have the raw form, small details can be changed by pushing the sharp edge with for example a small antler point. This is called “retouching”. Many tools are made of flint. The hunters and gatherers made blades, knives, arrowheads, and drills. They also made “composed tools”, using many very small flint pieces. The early farmers had flint daggers, axes, and sickles. Come and see how we knap flint in Albersdorf and how effective these very sharp stone tools are!

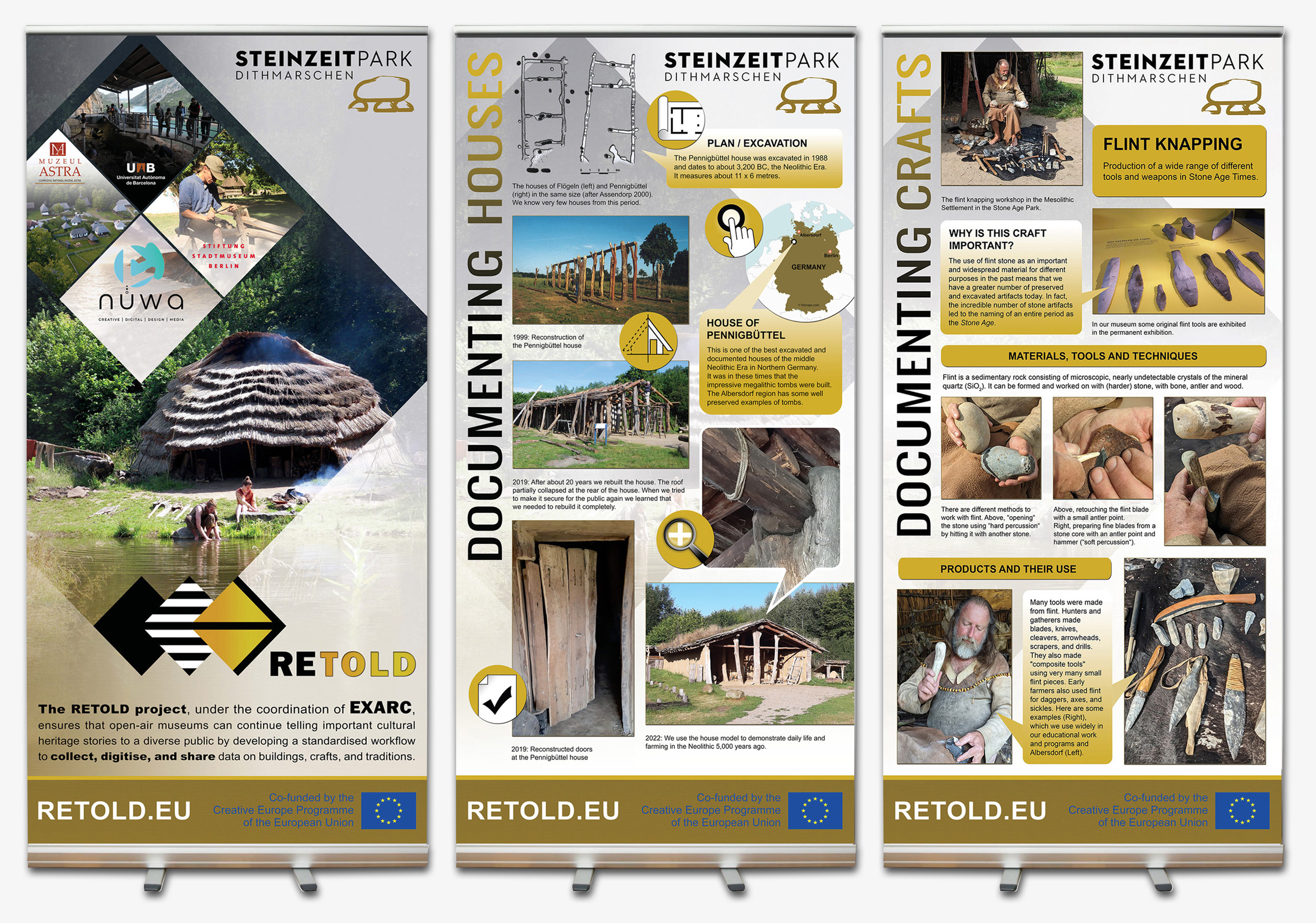

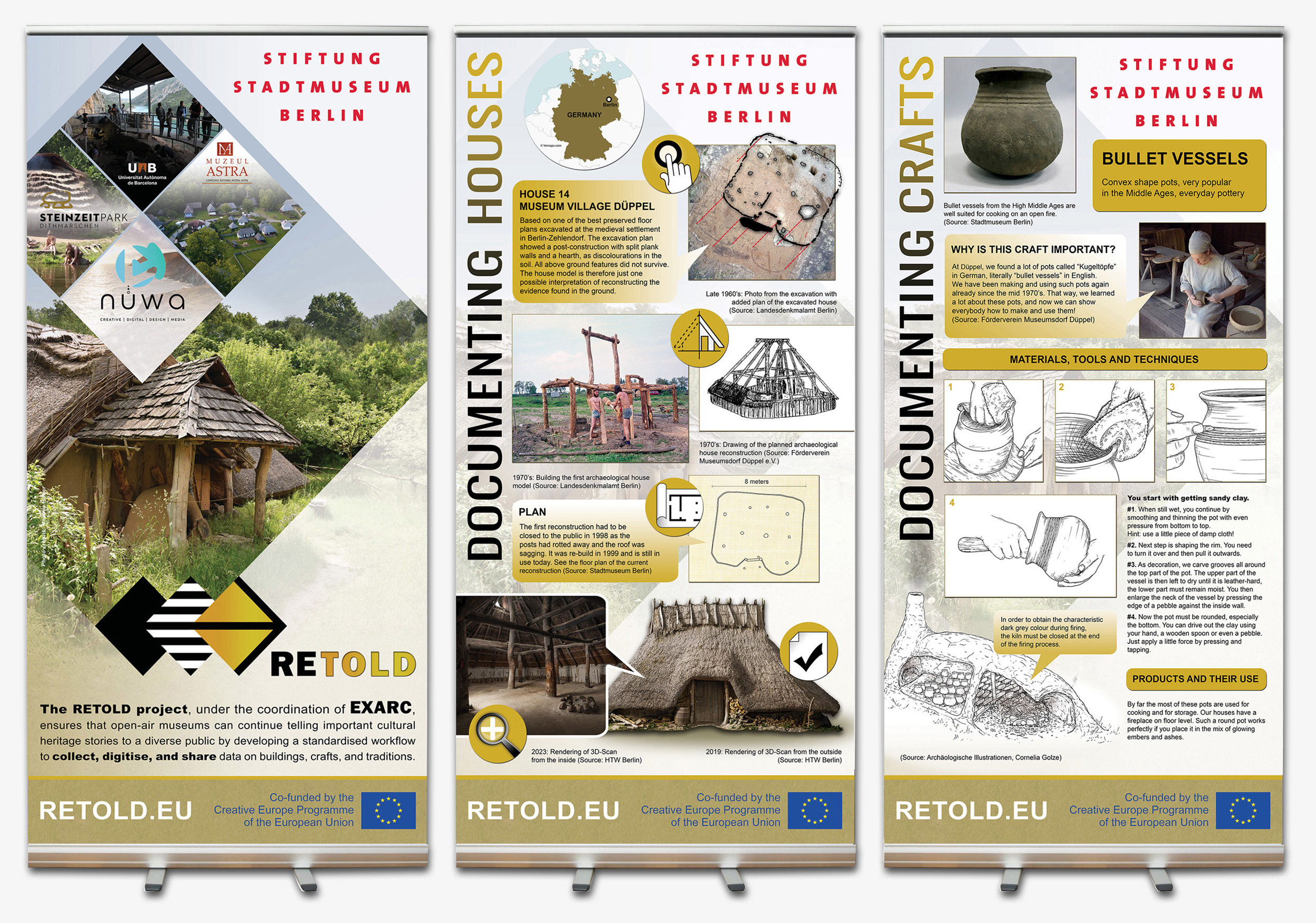

Case: Roll-up banners for visitors / stakeholders

Once you collected some text and images, following some basic questions,

you can present stories for example by means of banners.

As a try out, we decided we would collect information from all three RETOLD museums and present this, using banners. But it can as well be made into a flyer or a brochure (if you like to share a printed material). For all museums, the series of questions and the flow was the same. The questions were structured, following the same flow as we developed in our forms for documenting buildings and craft activities. We wanted to demonstrate that, once you have some basic info and footage about a craft or a building, this can be re-used and presented in different ways, depending on whom you want to present it to.

At the start, we thought the questions were very boring and straightforward, and we did not know how to answer them correctly. But when we followed up we found out, that these are actually the most commonly asked questions by visitors; our public starts from here. These questions give us the chance to pick up the quests, and let them tag along with us. We use these simple questions to open the doors towards immensely cool stories.

We made three series, one serie per year, and then times three as we had three museums. It was a test to see (a) if the museums could easily answer the questions and deliver the data in the right format and (b) if it was possible to turn this rigidly structured material into appealing stories, which visitors would appreciate.